JEFFREY WOLF

Over the summer and into early Fall, we created the ‘alpha’ version of the VERITRACE research platform and published it online. It can now be accessed here: https://research.veritrace.eu. It is also now linked to in the navigation menu on the VERITRACE website itself (‘VERITRACE Platform’).

Fair warning: the VERITRACE research tool is experimental, in an early version. The data and results should be used with caution and are not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. Nonetheless, the promise of the tool is already visible, and we are eager for scholars and researchers to try it out and provide feedback, especially on wished-for new features. In fact, there is a ‘Send Feedback’ button at the top of the website that is simple to use and will send an email directly to our team, with any comments and observations you have, while using the website.

The user has to register to use the tool, but the registration process is straightforward, requiring an email address and password. Once logged in, the user is presented with a tabbed menu at the top, which also includes a ‘Send Feedback’ button, which is the fastest way to send us feedback about the website:

As an introduction to the platform, I will briefly explain the purpose of each ‘mode’. I will save the Match and Search modes for last.

The EXPLORE mode – presented to the user after they login – contains summary data about the VERITRACE corpus, along with visualisations and charts of that data. The charts are produced directly from the underlying metadata of the VERITRACE corpus. We have not thoroughly ‘cleaned’ all the metadata yet, so this data is inaccurate in a number of ways, but it gives a general sense of the size and scope of the corpus.

The ANALYSE mode has not been implemented yet, but the various kinds of analyses that we wish to perform on the underlying data – including topic modeling, LSA analysis, and diachronic analysis (say, of semantic shifts in corpus keywords) – will be displayed here.

The READ mode provides a built-in IIIF reader that allows the user to read and study digital facsimiles of the printed texts that comprise the VERITRACE corpus. IIIF readers allow for loading more than one document at a time, providing the user the ability to compare two documents to each other, side-by-side, which can be handy. The VERITRACE research platform does not host, or store the documents themselves (often PDFs or images); these are generally stored on the source library’s servers, and the IIIF reader just loads them from there. Currently, the Bavarian State Library page images are loadable; the ones from our two other data sources still have to be implemented, but because the BSB is our largest data source, the user can already load more than 82% of the page images that constitute the VERITRACE corpus.

The final two modes have been the focus of our work on the website thus far, and so I will describe them in more detail.

The SEARCH tab allows the user to conduct varieties of keyword search throughout the VERITRACE corpus. We currently have 9 different kinds of search set up:

Most of these will be familiar to the user from using search engines, like Google, but I will highlight a few interesting twists. First, due to needs by members of the VERITRACE team, we implemented not just exact phrase and wildcard and fuzzy search types – which are standard – but an ‘approximate phrase’ search type, that, in a way, combines the two. It is more computationally intensive, but it allows for phrases and variations of those phrases to be searched for (and not just word variations). Proximity searches, grouping searches (which combine logical filtering criteria), and field searches – using the results fields we have included – will likely also be helpful for the researcher.

In addition to the act of searching itself, we have tried to make the results more helpful to academic researchers in a number of ways. First, we provide relevance scores and number of hits in every search result (they are not the same, though they are related), as well as up to 10 ‘snippets’ that show the search result in context, within that document. A few key actions – viewing the raw text of the document, loading the document in the IIIF viewer, and viewing ‘Results Analytics’ – are provided right next to the search result.

A note about ‘Results Analytics’: this is a separate panel that displays analytics about the set of search results.

This is particularly helpful given the number of documents in the corpus, so that many searches, e.g. for a specific term, will return hundreds of results (artificially limited to 500 at the moment), and thus the dilemma of comprehending the relevance of what has been returned. True, the results are ranked by relevance score, so the most relevant results should appear on top, but there are many cases where you want to get a sense of the overall results in their entirety, and this is what Results Analytics does. The user can adjust the relevance threshold to see more – or fewer – results analysed, for instance. They can view total number of matches and the languages of the returned results, not to mention data distribution, a list of top authors, and common terms, and even a list of the longest titles. We think this will make each set of search results more interpretable, without the user having to click through each one.

Finally, all result sets can be saved and exported, either as raw data (to be further processed) or in a nicely formatted markdown report – see an example from the beginning of such a report below:

And the results themselves in the report:

While there are more features one could discuss about Search, let’s move on to the final research mode: MATCH.

The MATCH mode is the most sophisticated and computationally demanding tool on the research platform. The goal is as follows: give the user the power to compare documents with each other, in order to find textual similarities at the sentence and passage levels (groups of 2-3 sentences). It is easiest to see how this works by taking an example. Let’s run a Match query using Newton’s 1718 English edition of his Opticks (on the left, below) and try to match similar passages in a comparison text, in this case the Latin edition from 1719 (Optice, on the right).

The image below shows what is going on: we have the Query text on the left and the Comparison text on the right. This is a single document comparison: 1 to 1. But the user could also perform a 1-to-many comparison (multiple comparison texts) and, eventually, a 1-to-corpus match, comparing a single text to all other texts in the VERITRACE corpus.

Below the choice of texts, there are quite a number of options in the Match Options panel that the user can review. We will likely make some of these editable at some point, but the point, for now, is just to show that each match relies on many different parameters, each of which could be tweaked. This reveals the complexity behind a single matching query.

Below the Options Panel, we offer a few kinds of match types and modes, which essentially provide standard sets of parameters that should meet most use cases.

An important distinction is key here: when we match texts to each other, we can do so using the vocabulary of the texts – their keywords, essentially – to find lexically similar passages. Or we can attempt to match semantically similar passages – based on semantic meaning alone, regardless of vocabulary used in either text. This is semantic matching. We need this, for instance, whenever our texts are in different languages as, by definition, most of the vocabulary will not be similar. But you can imagine, for instance with translations, the passages should rank quite highly on semantic similarity, while the lexical matching should be virtually nonexistent.

Our goal, then, is to provide the user a way of finding matching passages between, say, a French edition of the Corpus Hermeticum, and a later Latin edition, even with very little overlapping vocabulary, which is why we need semantic matching, in addition to lexical matching.

We also offer 3 different matching modes, from a comprehensive but slower approach to a faster, more selective one. This has to do, primarily, with the depth of the matching we choose to use.

And with these decisions made, we are ready to run the text matching itself. Right now, each match is conducted in real-time on our servers, so that it does take a little bit of time to get results. With longer and more numerous texts in the matching pool, the wait time can be considerable, and we will work on ways to improve performance dramatically. One option, which can only be done near the end of the project, is to pre-compute all the vector embeddings between all the texts using supercomputers, so that the results are already generated, and just have to be requested by the user. This would provide near-instant results, no matter how large the query.

In any case, let’s take a look at our results, for a standard semantic match between our query and the comparison text. What do you expect to see? They should be shown to be highly similar semantically, even if the two texts are not literal translations of each other. 18th-century translations could be quite loose, but with a technical text like Newton’s Opticks, we should see very similar semantic passages. And, that is what we get:

It took 22 seconds to run the query and 3.9 million comparisons were made (this will be made much quicker in the future).

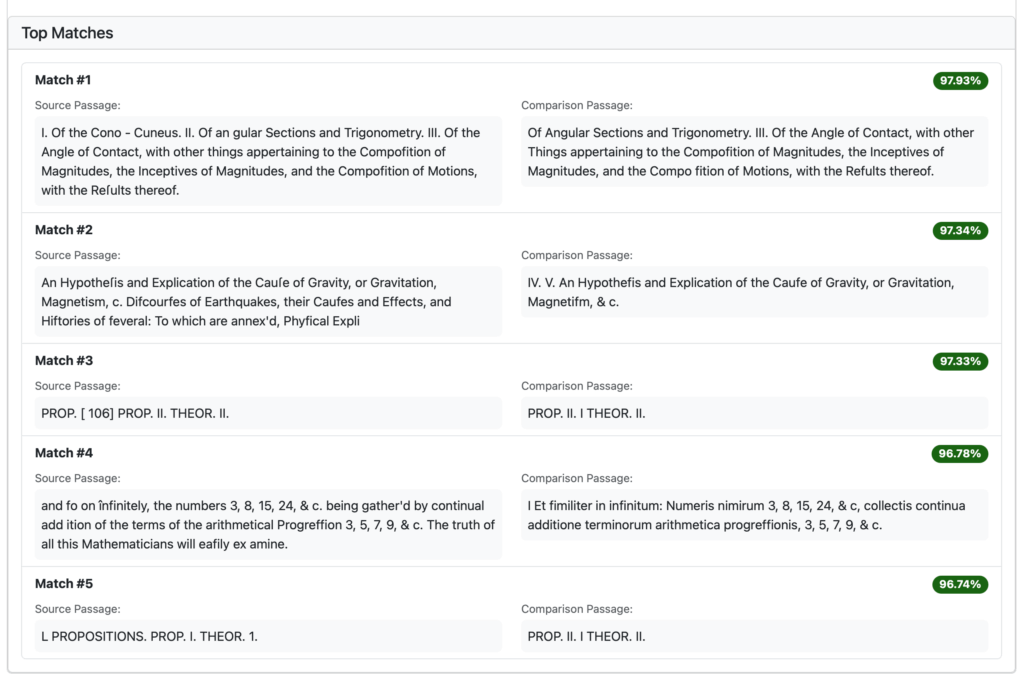

And below is what the top matches look like and – even with middling OCR quality texts – we can see that the system has identified what appear to be – on the left – the original passage in English and, on the right, its Latin translation.

In Match Details, we can review each potential match, side-by-side:

So far, the results are what we expect. What if we try this same match but run a lexical match instead of a semantic one? We expect that the matches will not be considered similar at all, given the lack of shared vocabulary. Is that what we get? Indeed, it is:

And, finally, if we run a lexical match of a text against itself – resulting in many highly similar lexical matches – that too meets expectations:

We provide automatic matching of keywords in the passages, side-by-side:

Now, even though this all looks very promising, more extensive testing of our system shows some worrisome results and unexpected outcomes. Our operating assumption is that the vector embeddings model we are currently using – chosen for simplicity, at first – is not sophisticated enough to handle all 6 languages in our corpus, as well as low quality text (due to poor OCR) in a number of cases. It leads, in some cases, to model collapse. Therefore, we are now testing more sophisticated and powerful vector embeddings, as well as trying to find effective ways to improve the quality of the texts we have, which will positively improve everything downstream of them.

Thus we still have plenty of work to do, but we are excited to release this very early ‘alpha’ version of the research veritrace tool, in order to solicit feedback from interested scholars and users.

So, create an account on our platform, explore the different sections, and send us your feedback. We look forward to improving the research platform in the months and years ahead.