Dr Jeffrey Wolf & Nicolò Cantoni

VERITRACE is a digital humanities project through-and-through. Because of this, it is worth saying something about why we think taking an approach from the Digital or Computational Humanities adds value to the intellectual research we are conducting.

To recap, the intellectual goals of VERITRACE are to answer the following research questions:

- How and to what extent did the ideas contained in the various ancient wisdom writings influence early modern natural philosophy?

- How did the various versions and editions of the ancient wisdom writings draw upon each other, and how were they appropriated and incorporated by their Renaissance promotors?

- In what fashion, and in what function, did these ancient wisdom writings return in the early modern natural philosophical discourse?

- How were the ancient wisdom writings, their authors, and their promotors perceived and discussed during the early modern period, in particular by natural philosophers?

It would not be feasible to answer these—especially at large scale and within a reasonable time frame—without the digital tools and approaches we are using. Let’s walk through a simple example.

One of our corpora of ancient wisdom writings is the Corpus Hermeticum—a collection of Greek writings ascribed to the ancient figure of Hermes Trismegistus. These writings, published in various forms from c. 1469, were first translated into English in 1650 by John Everard in The divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus, in XVII. books. Translated formerly out of the Arabick into Greek, and thence into Latine, and Dutch, and now out of the original into English; by that learned divine Doctor Everard (London: printed by Robert White, 1650). What was the influence of this translation on the next generation of thinkers? Can we detect specific strands of influence in publications written in English over the next 30 years? It would not be practical to read through every book published in English between 1650 and 1680—but, with transcriptions of these books in hand (courtest of the Text Creation Partnership and EEBO), we can conduct a systematic search for ‘traces of influence’ of the Everard translation.

A misinterpretation of our approach would be to think that, because we so heavily emphasise computational humanities, we therefore do not value, or at least undervalue, the traditional approaches of classical historical scholarship. Nothing could be further from the truth. In almost all cases, our digital tools present ‘breadcrumbs’ or avenues of inquiry that then must be followed up using traditional interpretative scholarship. Computers and AI are not—at least not yet—sophisticated interpreters of written texts, let alone historians in their own right. We are quite some way off from that. Digital tools and approaches remain complementary to the traditional work of historians and other scholars, allowing them to ask and answer questions that would not be feasible otherwise. A DH approach can enhance traditional scholarship—and that’s its true value.

Now, from an outsider’s perspective, PhD student Nicolò Cantoni will explore how this approach appears to him, new as he is to the field.

Nicolò Cantoni

The foremost reason I was instantly drawn to VERITRACE—and why, I suppose, I’m lucky enough to be part of the project—is that the revival of ancient wisdom during the Renaissance and early modern era has been the central theme of both my BA and MA theses. It’s a fascination that has accompanied me for half my life, even before the idea of pursuing a degree in philosophy ever occurred to me. However, while my formative years at the University of Pavia in Italy provided me with a broad and comprehensive view of the history of philosophy and ideas, digital humanities were not part of the main curriculum.

I had certainly heard of the term and had a vague sense of what it involved. The concept intrigued me. It also scared me away. It wasn’t that I was skeptical—rather, it seemed like something “other people” did (the “tech guys”), while I would simply continue to explore my research questions the old-fashioned way. Computers were never my passion; big ideas and research were. That was until VERITRACE entered the picture.

It’s now been 14 months since I joined VERITRACE, a project in which digital humanities tools are integral to our work. As an outsider, I took this as a welcome challenge and an opportunity to learn new skills. Sure, in the first few months I had to decode all the technical jargon, acronyms, and abbreviations just to follow basic conversations. That was expected and part of the learning process. Over time, as I expanded my vocabulary, the language of DH has gradually become more familiar.

I’m not easily swayed, but it didn’t take long for me to appreciate the immense potential of our methodology. DH allows us to sift through vast quantities of texts and data, far beyond what our limited human capabilities could manage. In applying digital research techniques to trace the influence of ancient wisdom in early modern natural philosophy and science, we are doing something that has never been done before. It’s something that pioneers of our field like Frances Yates could perhaps have only dreamed of, and their efforts were inevitably restricted by a necessarily human perspective. Standing on their shoulders, we now have the privilege of posing—or reframing—their questions and engaging with a Distant Reading Corpus that offers unprecedented access to historical texts. More than that, we benefit from over sixty years of academic inquiry and the high-quality research that scholars have produced in recent decades, and we have the opportunity to ask new questions that reflect the latest developments. As a team, we eagerly await the results of our investigation and are excited to interpret them. We will humbly leave our intuitions and presuppositions at the door, confident that the data will speak for itself.

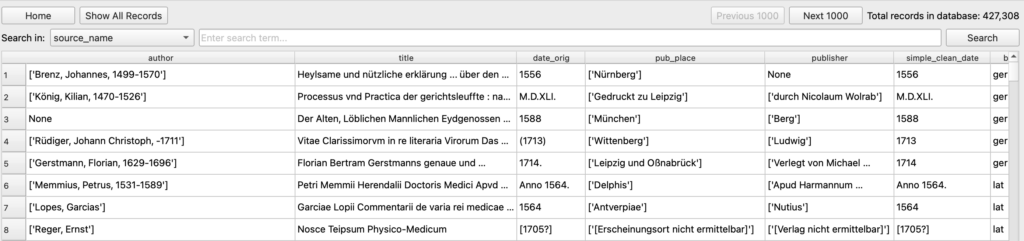

On a more personal note, over the last year, I’ve helped collect and manage our Close Reading Corpus, which mainly consists of the various editions of the Corpus Hermeticum and the Asclepius, Orphic Hymns, and the Chaldean and Sibylline Oracles that were printed before 1728. We’ve gathered approximately 140 texts in the online database tool Airtable, with links to their USTC pages (and other online catalogues), as well as to their digitalized copies. This work has given me a richer perspective on the editorial histories of these corpora, the ways in which they interacted with one another, and how they have been interpreted as part of the same discourse on ancient wisdom.

When I joined VERITRACE, I remember hoping that my humanistic background could help fuel such a digitally focused project. I am now equally excited by the ways in which the DH tools at our disposal will, in turn, help me explore and redefine the questions I’ve long sought to answer. To me, this is the true beauty and strength of VERITRACE: the synergy between human talent and creativity, and the potential of the machine, and how these two parallel processes will harmoniously enrich one another.