Eszter Kovács

These days almost everybody does “distant reading”, even if he or she has never heard or used this term, attributed to Franco Moretti, emeritus professor and co-founder of the Stanford Literary Lab. We do distant reading when searching a passage in a book, or searching for the source of a quotation, etc. (“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark”…) If we do not immediately remember where it comes from and try to find it on the internet, that is distant reading. If we try to find who said “I frame no hypotheses”, that is distant reading.

Even if distant reading is an everyday practice now, not only a research method, and it is also said to be detrimental to our memory, it cannot be as spontaneous in a research methodology as in everyday life. What we read distantly and how we perform this are crucial questions. Generally, we read distantly a corpus which is too large to be read but hides what we are looking for.

The first months of VERITRACE teamwork have been devoted to a better understanding of our close reading corpus and our distant reading corpus. While each of us studied the key texts of the project—the Chaldean Oracles, the Corpus Hermeticum, etc.—to find what early modern natural philosophers could take from these ancient wisdom texts, we also had a closer look at the huge textual ensemble in which influences may and should be detected. Numbers are high: the project Early English Books Online counts more than 146.000 titles, today’s Gallica en chiffres gives over 860.000 for books in the collection.

We keep raising methodological questions at this phase. Are entities of the distant reading corpus titles or books as physical objects? The number of printed books within the period we are studying is still very high. Another key question is OCR quality. In everyday queries, we are happy when we find the answer but when working on the digitised version of early modern print sources, we need to be conscious of the fact that results returned after a query depend on the OCR-quality. This aspect is also twofold: technical, since technological progress has changed the quality of the image over the past years, and social, since rapid and cheap mass digitisation often results in uneven quality.

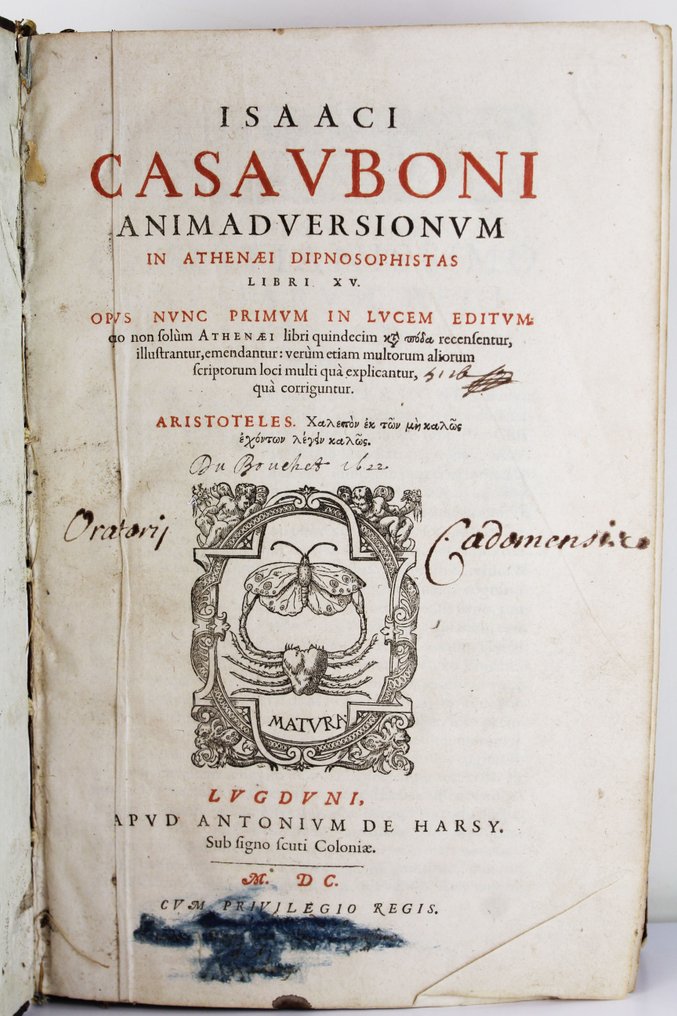

Another major question is how to work on bibliographic metadata. Even if it seems that metadata is easily available for databases such as Gallica or EEBO, we could see during our last work session that such a seemingly precise column as “date of publication” can be problematic when we retrieve datasets. Our current discussions focus on how to clean messy data regarding this field. And the question is not simply that of erudition. If we take as an example 1614, the year in which Isaac Casaubon demonstrated that ancient Hermetic texts were early Christian forgeries, we can see that it is not self-evident to retrieve from a database all works published before 1614 or published after it.

Without cleaning the date field, chronological order remains uncertain, and speaking about reception and influence remains imprecise. Let alone the fields author’s name, title, which will be the topic of forthcoming meetings…